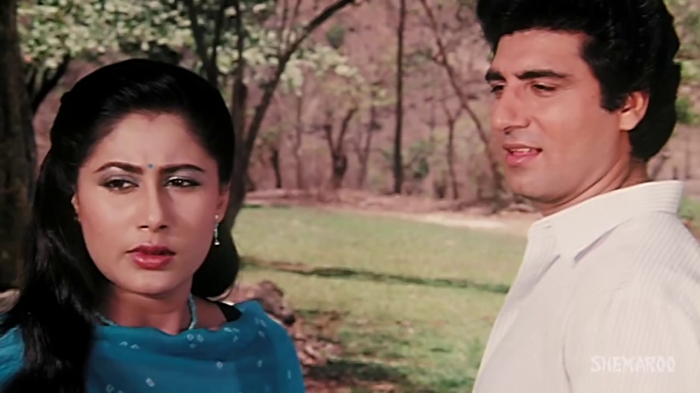

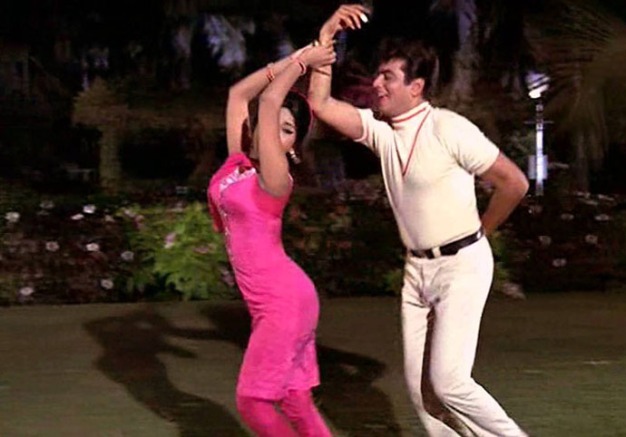

Nadira in her prime

The building set the tone for the meeting – a strong structure, beautifully detailed, gone to seed, the corridors dank and smelly. But the apartment itself was clean and comfy, decorated with exquisite period pieces.

Meeting Nadira was much the same. Clad in a shapeless housedress, her hair pulled back tightly in a bun, and no make-up, she was nowhere near the svelte, slinky man-eater we had come to associate her with from her roles.

But the moment she clasped your hand, you knew that she was still the same tempered steel, so known to us from her many famous films.

Her tongue was still razor sharp too, and she would take no nonsense whether it was from the press or from the local plumber who was there to fix a leaking tap.

She mistook my initial attempts at smalltalk for diffidence. “Look, dear,: she said. “If you want to ask any daring questions, go ahead. Don’t be afraid!”

I didn’t have the heart to tell her that the editor who had commissioned me to write the article, Dinesh Raheja, a veteran film journalist and then editor of Movie magazine, had just wanted a piece on stars in their twilight years, and not a tell-all rip-off.

And yet for all that, she was very vulnerable. In between our conversation, while talking about how she spent her time then – this was sometime in 1988, when she had not worked in about four years, the last time being Ramesh Sippy’s ‘Saagar’ – she suddenly broke down and said, “Do you know I buried my last living blood relation, my aunt, on the 27th of September?It was a terrible feeling. Today I have nobody.”

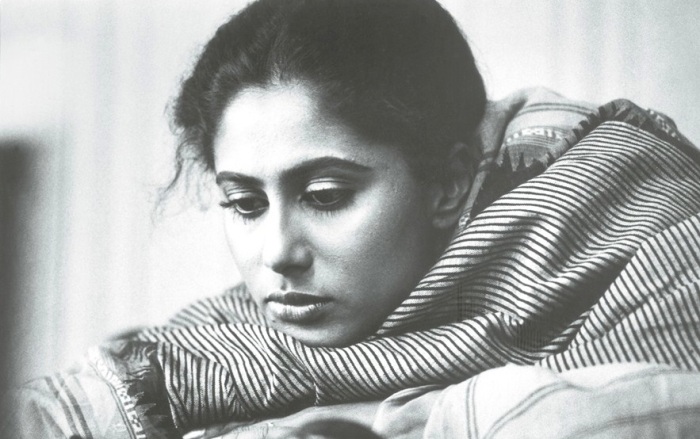

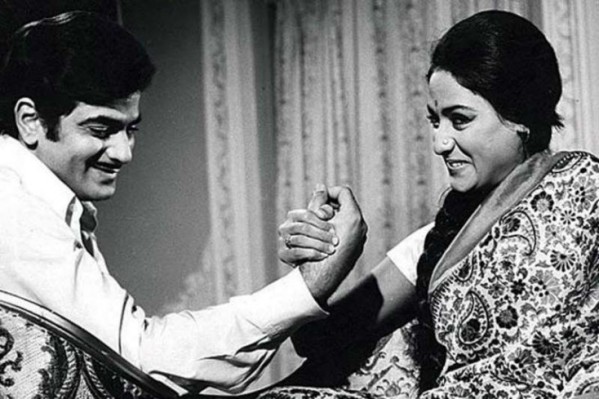

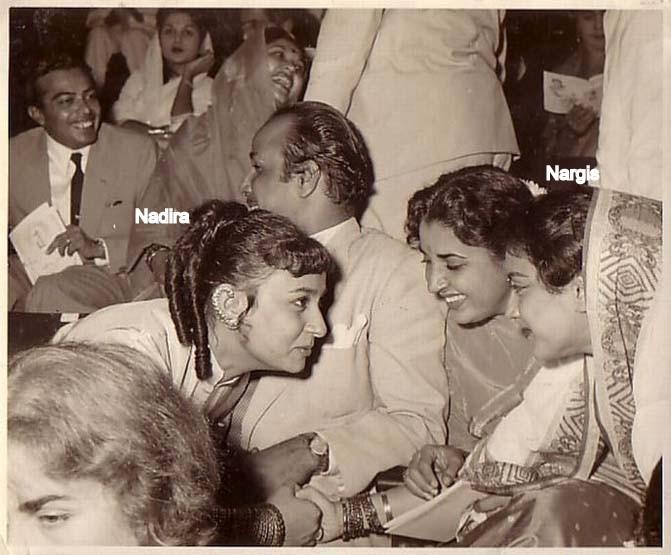

As Nadira was when I first met her

The loneliness was palpable, and the agony searing. She lived all alone in her apartment near Kemps Corner, in south Mumbai, with her 70-year-old housekeeper and caretaker Maria, surrounded by her books, artefacts and memories.

And yet, she didn’t make much of her loneliness. “I’ve lived with pain,” she said simply. “Of course here in the film industry (the word Bollywood hadn’t been coined then) everything is exaggerated. When you become famous they make so much of you that it’s suffocating. They don’t let you breathe. And then, one day suddenly everything is taken away and you are left with nothing! So naturally stars feel their loneliness more.”

Though the words and tears flowed freely, in retrospect I feel that Nadira was mourning the lost opportunities more than wallowing in self-pity. She’d never realised her full potential in an industry that couldn’t make up its mind about what to do with her talent. She’d been slotted in vampish roles when, after her debut in Mehboob Khan’s ‘Aan’, she chose to play Maya in Raj Kapoor’s ‘Shree 420’. “I couldn’t be bothered, dear,” she said when I asked her why she didn’t pursue better roles in the wake of her early success. “They asked me to hire a secretary or manager, but I didn’t want any of that. I wanted to live my life my way, not follow someone’s dictates. I don’t regret it at all.”

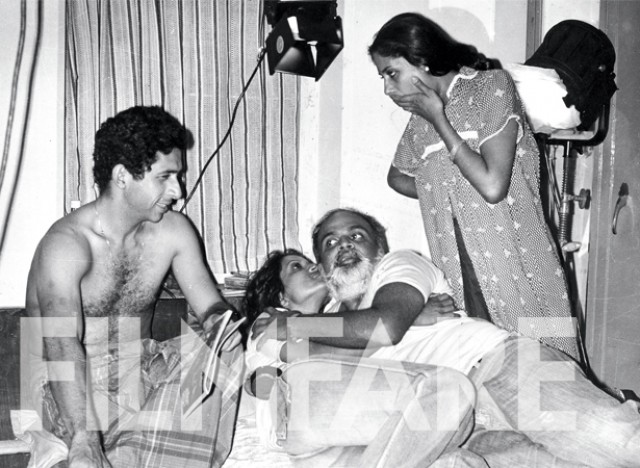

Gossiping with character actress Shammi and Nargis (at extreme right), probably at a show of ‘Shree 420′. The man in the middle is character actor Anwar Hussain, Nargis’ brother.

I didn’t know it then, but her real name was Florence Ezekiel, and born to Jewish parents. She’d been married to a writer who’d migrated to Pakistan after the partition, I heard much later, or so said an old film distributor at Naaz Cinema Building in Tardeo, Mumbai. It was then the nerve centre of the Bombay film industry – most deals were made or broken there, and he was a storehouse of industry lore. He also said she’d been married a second time, very briefly, only to be cheated again by a gold-digger.

It was apparent even at my first meeting that Nadira was an easy touch. She didn’t think twice before revealing whatever was on her mind; she didn’t feel the need to hide anything. Lonely, she most certainly was, but it was for companionship – she wanted to discuss books, her biggest weakness, and then, films, a distant second. When she was alone, her drink gave her company – vodka poured over freshly squeezed sweet lime. Maria was ordered to get me a glass as soon as we’d settled down. Within the next couple of hours we’d downed more than a couple of tots, – I had to secretly signal Maria to make mine plain lime juice after that. Round and jolly, Maria nodded silently, shaking with mirth. I could see why they got on so well.

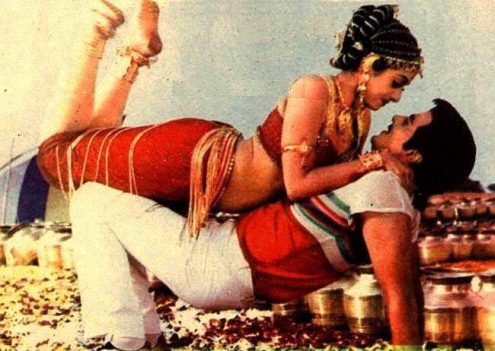

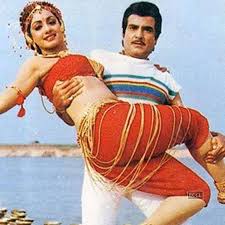

The spitfire in ‘Shree 420’ was to typecast her forever

I never did write that story for Dinesh. I was quite shaken emotionally, and was afraid I would put too much of myself into it. At least that’s what I told him. I realise now that I just didn’t want to expose Nadira to the pity that the article would have aroused.

When Dinesh told her that I’d been upset after the meeting, she wanted to send me flowers. Those days I didn’t even have a telephone connection, nor an office address (I was between jobs then) so I can’t claim to having received flowers from Nadira. But the next time I passed her apartment building, I dropped in on her and was received with much warmth.

This time we talked about loneliness, and she told me she didn’t feel lonely in the sense that she needed somebody beside her. “I would certainly like someone who understands me and accepts me for who I am,” she said. She paused, listening to her own words, and smiled with irony. “Like, who wouldn’t, right?” It was morning but that didn’t stop the vodka-laced sweet limes. Strangely, there was never a moment when she was drunk. The drink only appeared to make her more clear-headed and lucid.

One of her better roles in Kamal Amrohi’s ‘Pakeezah’, which was also Meena Kumari’s swan-song

There were moments when her vulnerability slipped through. Once she looked at herself and said, “I am so dark.” Which was absurd; she was a hundred shades lighter than any light-skinned person I knew. When I protested, she drew her head up in the imperious gesture so familiar to her fans. “That’s because you haven’t seen my mother, dear,” she said. “She was so fair! She used to call me her black duckling!”

Did her childhood have anything to do with why she pursued unhealthy relationships? Having been a Psychology major, I thought I knew it all, but when I hesitatingly mentioned it, she gave me a pitying look. “No, dear, that’s not it at all. I had no such trauma; though we had little money I was very happy as a child.”

Later, she elaborated why she found it hard to have steady relationships.

“I am wary of new relationships,” she explained. “I am tired of being exploited. The problem with me is that I only see the virtues in a person at first. Then I shower that person with gifts so that I can possess him quickly. He takes it as my weakness, not kindness, and takes advantage of me. Then I see through the person, and lose interest.”

All through this half-morbid self-analysis, Nadira kept flitting between other subjects, her razor-sharp wit providing some much needed relief.

With Nadira, as with other faded stars, it was a constant battle between the image she wanted to project and the person she really was. One instant she would claim with icy calm: “I am not suicidal or praying for death. I can’t do social work and it is too late now to adopt a child. I am not a recluse, but I don’t want to get involved anymore.”

And then the next moment, she would add: “Sometimes I do stretch out, but I don’t want to be a burden to others. I do have a few friends who would give their left arm for me, but they are all so far away…. You know, sometimes I buy myself a pair of shoes, or socks or handkerchiefs. It’s silly, I know, but it’s nice…”

Illusions are a star’s best friends, but Nadira was past all that. “What is left in me for people to come to me with an ulterior motive?” she laughed once while we were talking. “I only have my intellect to give!”

But the need for somebody to love, to care for, was still there. “I am not playing lonely,” she stated simply. “It’s a physical loneliness. Someone to care for you, to get tea for. That’s what I miss; a partner in life.”

She spoke bravely of living as a fight, as much against loneliness as anything else. And in the next instant she broke down, saying, “I’ve surrendered; who do I fight? The walls?”

And then just as suddenly her mood lightened as we spoke of Sundays and holidays. “Monday, Tuesday, what does it matter? Every day is Sunday for me! She laughed. “My only communication with the world is my morning walk, when I meet others and say, hello, letting them know I am still alive!”

Work was her only remedy, but there was predictably not much of that. “Of course, I am lucky that I’ve always got something when I needed it,” she said. “Just the other day I got Rs.5,000 for dubbing for a film. Of course, I need the money, but I need the work more. You know, my dear fried David (the late character actor), who was like a father to me, always told me never to ask for work. But I’ve even done that. I was born with talent, but who’s using it? I am not that gone after 40 years in films to act as an extra!”

Between alternating bouts of joy and sorrow, Nadira came across as a much stronger person than she would have me believe. One day she called me to say that she was being presented an award by some organisation that night. “I am so excited about tonight, and so frightened,” she said. “I’ve received so many awards, but still… I am going to go alone, proudly, maybe in a taxi. I am very self-sufficient. And worst comes to worst, I’ll walk back home.” And that’s exactly what she did that night. She dazzled them all, and came back resplendent and glowing in that aftermath of that warmth.

Nadira was a survivor. And that’s the greatest compliment one could have paid her. My only regret is that I didn’t when I had the chance.